-

The Romans, the Wall and the Wildlings

THE ROMANS, THE WALLS AND THE WILDLINGS

History Behind Game of Thrones

Game of Thrones has become one of the most popular books in the genre of fantasy, and the most watched show in HBO history.1 George RR Martin has gained a celebrity status that very few authors experience. According to Joseph Abercrombie, a major figure in British fantasy, Martin has revolutionized the genre of fantasy, making it appealing to a wider audience.

As readers of this website are well aware, Martin is very familiar with history from the ancient world to medieval Europe and draws much of his inspiration from these periods of history. He creates a new universe that brings together aspects from all areas of history and culture and makes a benevolent type of pseudo-history or fictive history.

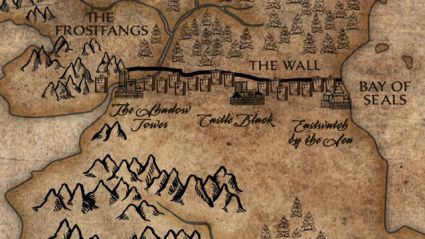

The Wall stretches for 100 leagues (300 miles) along Westeros’ northern border, ostensibly defending the realm from the Others. In practice, the Wall is a partition that segregates the wildlings from those who shelter south of it. Image: © HBO.

In Martin’s depiction of the Wall, the wildlings, and the North, he recreates the Roman perception of the native Britons as the ‘Other’ – a distancing strategy employed to dehumanize, alienate, exclude and justify ill treatment of groups outside of one’s own.

The Wall might just be the most direct inspiration from the ancient world in Game of Thrones. Martin himself has said, in this article, that the inspiration came from his visit to Hadrian’s Wall, and it was during this time that he wondered, “what it would be like to be a Roman centurion from Italy, Greece or even Africa, covered in furs not knowing what would be coming from the North.”

The map of Westeros can be interpreted as England and Ireland inverted to create the western continent.

In both England and Westeros, the Walls run across the narrow parts of the land stretching from coast to coast. Hadrian’s Wall was built during the reign of Hadrian in the second century AD, which is often defined by its architectural and engineering achievements. The Roman wall was 80 miles long and 20 feet in height2 .

When building Hadrian’s Wall, the Roman surveyors exploited features in the natural British landscape. Part of the wall in County Durham and Northumberland, for example, is built along the Whin Sill — a sheer cliff on the northern face of Hadrian’s Wall3 .

Hadrian’s Wall facing east towards Crag Lough lake in Northumberland, England. Image: Michael Hanselmann on Wikimedia Commons.

Originally, some sections of Hadrian’s Wall towered 20 feet high. As John-Henry Clay mentions in his article on this website, because Hadrian’s Wall exploited the landscape, those approaching from the north would have perceived the Wall as soaring an additional 100 feet or more towards the sky, making these sections seem colossal.

Bran the Builder. Image: © HBO.

In contrast, when Brandon the Builder constructed the Game of Thrones‘ Wall 8,000 years ago , it was entirely made of ice and stood almost 700 feet high and 300 miles long4 .

When Jon Snow approaches the Wall with the wildlings, after infiltrating their camp, he notes the deceptive height of the Wall, where the height changes in certain spots: “Brandon the Builder had laid his huge foundation blocks along the heights wherever feasible, and hereabouts the hills rose wild and rugged.”5 Brandon the Builder seems to have employed the same techniques as Hadrian such as using the natural landscape to his advantage, which gave additional height to the north side of the Wall.

Castles Defend Both Walls

The system of castles across the Wall is also reminiscent of the forts and mile-castles along Hadrian’s Wall. At every fort and mile-castles there was a gateway that acted as a check point to control movement and goods between the north and south of Britain.

The Roman forts, which were every seven to eight miles, were larger settlements that had both a main military fort and outside civilian settlement.6 The mile-castles were small forts at intervals of a Roman mile that were defended by a patrolling garrison who would be able to quickly respond to any distress or situation.

The location of the Wall in Westeros (top) and the Roman Wall’s location (bottom).

Along the Game of Thrones‘ Wall, there are nineteen castles, three of which remained manned while the others were abandoned with their gates sealed.7 The Game of Thrones’castles were strictly for defensive purposes. They didn’t have the extra amenities of Hadrian’s Wall.

For both the people of Westeros and Roman world, the walls marked the end of the world. Martin’s Wall likely recreates what Romans who had never set foot in England might have imagined.

The Roman wall was in the farthest corner of the world, dividing the civilized Roman world from barbaricum.8

North of the Walls is Deadly, Savage and Alien

In the fourth century, increasingly untenable military threats to the Roman Empire and other problems, led the Romans to abandon their British posts9 .

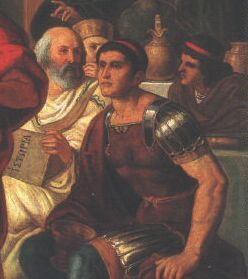

Priscus (left) with the Roman embassy at the court of Attila the Hun, holding his ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ (History, which the painter has incorrectly spelled ΙΣΤΩΡΙΑ). (Detail from Mór Than’s Feast of Attila.) Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By the sixth century, Hadrian’s Wall moved out of Roman reach — and the Roman perception of Britain and Hadrian’s Wall would have changed from the time it was built. Procopius, a sixth-century Roman historian, gives a fantastical view of Britain, one that would fit in with Martin’s vision:

in the island of [Britain] the men of old built a long wall, cutting off a large part of it; and the climate and the soil and everything else is not alike on the two sides of it. For to the south of the wall there is a salubrious air, changing with the seasons… many people dwell there, living in the same fashion as other men. But on the north side everything is the reverse of this, it is actually impossible for a man to survive there and every other kind of wild creature occupy this area as their own. The inhabitants say that if any man crosses this wall and goes to the other side, he dies straightway, being quite unable to support the pestilential air of that region, and wild animals10

The atmosphere differed significantly between the south and north, according to Procopius. This can also be said of the Seven Kingdoms in comparison to the areas beyond the Wall.

In the Seven Kingdoms the seasons change, although their season sometimes lasted years. But, beyond the Wall, it’s always cold. The terrain makes it difficult for those who don’t know it to survive11 .

Dangerous beasts – and where to find them

In addition to the atmosphere, the north has dangerous creatures and beasts that are unknown to the Seven Kingdoms, creating a polar divide between the north and south similar to Procopius’ description of Britain.

Old Nan (Margaret John) would entertain Bran (Isaac Hempstead Wright) with scary stories about the Others during his convalescence, something characters like Tyrion might deem to be Snarks and Grumkins. © HBO.

Bran Stark, the younger child of the Lord of Winterfell, would hear tales from his old Nan about monsters, giants and ghouls beyond the Wall, but they could not pass as long as the Wall stood.12 This is an example of rumor and tales that go along with unknown parts of the world; however, in Game of Thrones some seem to be true.

In Roman literature, there are often mythological perceptions and stories, such as the one given by Procopius, about things beyond the known world. The stories and perceptions become more skewed over time and distance.

The Romans believed that Rome was the core of culture — and the peripheries did not have any, especially in the western provinces. (This is similar to the people of King’s Landing’s perception of themselves compared to the North and beyond the Wall.)

Beyond the Wall Lurk Barbarians

Britain was the edge of the known world and beyond Hadrian’s Wall was barbaricum, just as for the people of the Seven Kingdoms the Wall was the end of the world. The free folk or ‘wildlings’ are a race of people beyond the Wall; they call themselves free folk while the people of the Seven Kingdoms dub them wildlings. The wildlings are separated by the Wall and are seen as primitive, wild and savage peoples.

The Wildings: specifically, Rattleshirt (either Edward Dogliani or Ross O’Hennessy) and his war band. Image: © HBO.

The wildlings have similar societal structures to the pre-Roman Britons or Scots: chieftain societies organized in tribes and clans which were not politically unified13 .

The people living in the north and west parts of Britain had small villages and lived in roundhouses or huts and encampments with no permanent cities by Roman standards.14 The ‘civilized’ people of the southern kingdoms describe the wildlings and their way of life using language similar to that of the Roman ethnographers.

The Roman historian, Tacitus, describes north of Hadrian’s wall by writing “it is a savage place.” Another Roman, Horace, describes them as “the fierce inhospitable Britons who live there.”15 The majority of Roman writers give the same stereotypical description of the people as brutes, savage, lawless, warlike people, primitive, tent-dwellers16 .

The Wildling’s camp. Image: © HBO.

These writers emphasize the uncivilized ways of those north of the Wall, a sharp and likely deliberate contrast against that is contrasted to the Roman perception and notion of the civilized. The same is said for Game of Thrones, the people in the south have both a fear and hatred for the wildlings and circulate stories of their savage cultures. In one example Bowen Marsh says to Jon Snow, “These are wildlings. Savages, raiders, rapers, more beast than man,”17 and these types of descriptions carry on throughout the novels.

The sources on early Britain come from external writers, the majority neither living in Britain nor being of British origin, since very few to no written sources survive from a native perspective.18 The views of the Britons is generally skewed and biased, since the Romans also lacked a type of anthropological participant observation study on the Britons that would give a primary account of the inner workings of the society.

Mance Rayder (Ciarán Hinds) is the King-beyond-the-Wall. Image: © HBO.

In Game of Thrones, Jon Snow’s perspective on the wildlings is that of an outsider, a man from Winterfell and not North of the Wall. Jon Snow infiltrates Mance Rayder’s camp and lives as one of the wildlings to uncover why they are uniting under Mance Rayder’s leadership. “Ride with them, eat with them fight with them, the ranger had told him, the night before he died. And watch.”19

When Jon enters the wildlings’ camp, he notices their tents made of skin and hide, and makeshift shelters. He sees their warlike nature, men and women making primitive weapons and spear heads, as well as fighting each other20 .

When Jon begins to live among the wildlings, he still believes that “they have no laws, no honor, not even simple decency. They steal endlessly from each other, breed like beasts, prefer rape to marriage, and fill the world with baseborn children.”21 Yet he quickly became fond of Tormund, sharing stories and learning the customs of the wildlings.

Jon becomes part of the Wildling tribes, as his clothes in this image reveal. © HBO.

Initially, Jon still believes the southern stereotypes of the wildlings as savage brutes constantly fighting. But after living with them, observing them and pretending to be one of them, Jon realizes that the wildlings are just like everyone else. They are looking for safety and are in need of protection from the beings in the north.

Although their society has a different structure and way of life, they are not unlike people in the south. Jon begins to respect and care for the wildlings, he learns from Tormund, he grows to admire Mance Rayder and falls in love with Ygritte. But, ultimately, his heart, and loyalty, remains with the Night’s Watch.

Jon and Sam exchange dubious looks as the wildlings enter Castle Black. Jon’s men were not amused by his decision to shelter the their historic enemy within their stronghold. Image: © HBO.

Once Jon becomes commander of the Night’s Watch, he announces an alliance with the wildlings. He proposes letting some wildlings pass through the Wall to protect them from the beings of the north, which is not a popular idea with the other men of the Night’s Watch.

The Wildings enter Castle Black. © HBO.

When arguing with Bowen Marsh about his decision to let the wildlings pass, Jon defends them after Bowen calls them savage beasts and rapers: “Tormund is none of those things, said Jon, no more than Mance Rayder. But even if every word you said was true, they are still men, Bowen. Living men, human as you and me. Winter is coming, my lords, and when it does, we living men will need to stand together against the dead.22 ”

The Romans did not have the same insight into the lives and societal makeup of the native Britons, but a similar situation in the Roman world is in the instance of the Huns in the fifth century AD. They were often described as the most barbarous of the Roman enemy with very little civilization, not even making use of fire23 .

The Roman writer Priscus was able to observe the court of Attila the Hun during a diplomatic mission and gives a completely different view.

The full version of nineteenth-century painter Mor Than’s Feast of Attila.

Although Priscus was in Attila’s court for a far shorter time than Jon Snow is with the wildlings, Priscus had the opportunity to observe and discuss Hunnic customs and differences from the Romans with a member of Attila’s court.

Priscus concludes that, even though the Huns are living very non-Roman lives, they are a human enemy and are not as barbarous as one might think.24 Jon Snow comes to the same conclusion about the wildlings: they’re humans and not the monsters they are made out to be. Priscus only glimpses the Hunnic society whereas Jon Snow assumes the guise and inserts himself as a member of the wildlings’ society. Jon grows to respect some of the wildlings, even though they have distinct cultures and are different from the men of the south, he recognizes that they need help, and tries to make decisions for the greater good rather than personal prejudices. Jon Snow is basically a Roman who gets the opportunity to explore beyond the Wall and observe and partake in the society of the Other.

George RR Martin explores history in a unique and different way. He blends many different eras of history into one and seamlessly creates an alternate reality that both reflects historical societies and creates a new fantastical universe.

The area to the north of the Seven Kingdoms has the most obvious connection to the Roman world. Martin’s inspiration for the Wall comes from Hadrian’s Wall, and many similarities rise up in its construction and the system of buildings. In addition, the descriptions of the wildlings are similar to the Roman ethnographers, both categorized the Other as brutes, savage and primitive peoples.

Jon Snow, however, is able to give a description of the wildlings’ life, culture and needs, while the Romans lack this type of source in the society of the Britons. Martin takes elements of Classical society and perceptions, he enhances them to make mythology and misconception into reality. The Wall and the wildlings both reflect historical reality for the Britons and Romans, but Martin changes and exaggerates them to create a new universe in the epic fantasy genre.

- Many thanks to Jakub Czyzowski for his help. [↩]

- Mattingly, D. J. An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC-AD 409. London: Allen Lane (2006), p. 156-157 [↩]

- Liss, D., W. H. Owens, and D. H. W. Hutton. “New Palaeomagnetic Results from the Whin Sill Complex: Evidence for a Multiple Intrusion Event and Revised Virtual Geomagnetic Poles for the Late Carboniferous for the British Isles.” Journal of the Geological Society 161.6 (2004): 927-38, p. 60. [↩]

- Martin, G. R. R. A Game of Thrones. New York: Bantam Books (1996), p. 184. [↩]

- Martin, G.R.R. A Storm of Swords. New York: Bantam Books (2000), p. 406. [↩]

- Harrison, D. Along Hadrian’s Wall. 2nd ed. London: Cassell, 1975, p. 16-17. [↩]

- Martin, GRR. A Storm of Swords (2000), p. 758. [↩]

- Mattingly, An Imperial Possession (2006), p. 8. [↩]

- Meyer, A. “Theodosius to Theodosius II.” CS 3490F: Late Antiquity 284-800. Fall 2015. [↩]

- Procopius of Caesarea, History of the Wars, VIII.20.42-48. [↩]

- Beyond the Wall is split up by the Frostfangs (a mountain terrain), the Haunted Forest, and the Land of Always Winter farther north. [↩]

- Martin, GRR. A Storm of Swords, 2000, p. 770-771. [↩]

- However, in A Clash of Kings, the times are defined by political uncertainty and conflict, we learn that the wildlings are uniting under the King beyond the Wall, Mance Rayder. [↩]

- Although the archaeological record suggests something more complex (Greene, E. “Roman Conquest of Britain” CS 3555E: The Archaeology of the Roman Empire. February 28, 2016.).

[↩] - Tacitus, Agricola, VIII; Horace, Odes, III.4.33. [↩]

- Mattingly, An Imperial Possession, 2006, p. 34. [↩]

- Martin, G.R.R. A Dance with Dragons, New York: Bantam Books (2011) p. 572. [↩]

- Mattingly, An Imperial Possession, 2006, p. 25: written by an alien elite with a Roman cultural agenda. [↩]

- Martin, A Storm of Swords, 2000 p. 210. [↩]

- Martin, A Storm of Swords, 2000, p. 94-95: Men and women are equal in wildling culture. [↩]

- Martin, A Storm of Swords, 2000, p. 208. [↩]

- Martin, A Dance with Dragons, 2011 p. 572-573. [↩]

- Maas, M. Readings in Late Antiquity: A Sourcebook. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, (2010), p. 373. [↩]

- Priscus, Fragment, 11.2. [↩]

Tags : GoT, Roman Britain, Hadrian's Wall, Barbarians

Tags : GoT, Roman Britain, Hadrian's Wall, Barbarians

-

Commentaires

Keep calm and study British history